PepsiCo recently made waves with its purchase of SodaStream, but the company is now making news in the food business. This time the news is all about Pepsi’s Frito-Lay division, and its mischief making Chester Cheetah and his crunchy, cheesy, Cheetos brand. Pepsi recently sent a cease and desist letter to World Peas, a

Pepsi

Owning Some TM Happiness: Bubly ≠ Bubbly?

For a few months now, the Minneapolis skyway system has been flooded with a variety of fresh, creative, eye-popping advertising to promote Pepsi’s new bubly sparkling water collection:

Although not a lie (the bottles I’ve seen clearly reference Pepsi), you’d never know from this ad or the trademark registration that Pepsi is behind bubly, since…

Bringing Down the Bauhaus for Trademarks?

We’ve been spilling a lot of digital ink lately on the topic of non-traditional trademark protection and how the functionality doctrine serves as an absolute bar for such protection.

As you know, for some time, we’ve been stressing the importance of close collaboration between trademark and marketing types when it comes to forming public communications…

Take Down for “Chinatown”?

-Wes Anderson, Attorney

Famous brand owners, take note: a Turkish artist and designer named Mehmet Gozetlik recently released “Chinatown,” a mesmerizing series of photographs in which neon lights depict famous design marks, with the word mark replaced by its generic wording in Chinese. Is your brand one of them?

The Pepsi logo, for example, has…

Description of a Trademark with the USPTO

Continuing our discussion — from yesterday and the day before — about the description of a mark provided to the USPTO during the registration process, the below images from two unrelated federally-registered, non-verbal logos for banking services, help tell another related story:

As the links…

Pepsi Gets Grip on MLB All-Star Extravaganza

How cool is it to have the MLB All-Star Game and related events, right here in Minneapolis? Very.

How cool is it to have the MLB All-Star Game and related events, right here in Minneapolis? Very.

As the advertisement shows, Pepsi is playing a large role in the event, as the “Official Soft Drink” of the MLB All-Star Game.

As attractive as the ad is, sadly, I suspect that only trademark types and…

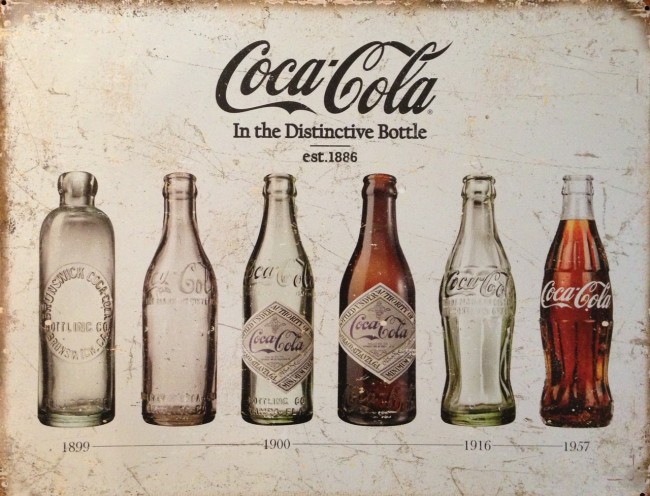

The Most Famous Bottle Design, Forever?

Coca-Cola settled on its famous contour bottle design almost 100 years ago, in 1916, after several years of trials with other far less distinctive shapes (at least under today’s standards):

Federal trademark registration data confirms the first use date to be July 8, 1916. The description of the contour bottle design mark in 1960 was:…

Federal trademark registration data confirms the first use date to be July 8, 1916. The description of the contour bottle design mark in 1960 was:…

A New Generation of Storytelling: Getting a Grip on The New Pepsi Bottle Design

The importance of “storytelling” seems to be the buzzword lately when it comes to branding communications and decisions. For example, last August Branding Strategy Insider wrote that “Brands Must Master the Art of Storytelling,” and just last week it wrote twice on the subject, about “Shared Values in Brand Storytelling” and…

Pepsi, No Coke: Branding Nonsense at Work?

Irony is something I enjoy capturing, as you already know, especially when it comes to branding. Take this recent image from my favorite hot dog joint in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Yesterdog:

Note the vintage Drink Coca-Cola signage on the wall, directly behind the modern soft drink fountain, delivering only Pepsi products, to my…

Taste Infringement?

We’ve spent some time here discussing the world-famous Coca-Cola brand. Most recently, David Mitchell wrote about the incredible consistency of the Coca-Cola brand over the past 125 years. A while back Dave Taylor wrote a nice Ode to the Brand of Brands, the King of Cola: Coke.

And, let’s not forget my humble suggestion that a roadside sign promoting Coca-Cola at a drive-in restaurant that actually sells Pepsi instead of Coke, might be a good example of an appropriate application of the initial interest confusion test.

But, what about Coca-Cola’s frequent reference to "taste infringement" — some cleverly novel and suggestive legalese apparently coined by the Coca-Cola brand a few years back with its launch of Coke Zero?

Putting aside Brent’s fair question of whether the ads are a good idea, some of my favorite ads have been the Coke Zero viral ads, where a variety of lawyers are punk’d on hidden cameras, led to believe they are being interviewed by Coca-Cola representatives to take legal action for "taste infringement" — against the Coca-Cola team down the hall, the rival team of co-workers behind the Coke Zero launch. This one is my favorite, with lines such as these:

"Are you aware that Coke Zero tastes a lot like Coca-Cola?"

"There might be some taste infringement issues."

"I think it’s basic taste infringement, I’d like to stick with that phrase."

"Basically, a patent/copyright, a little too closely."

The ads are silly and I suspect most viewers appreciate the ridiculousness of Coca-Cola suing itself, but I’m not so sure people understand "taste infringement" to be a ridiculous or faux-legal claim — especially in this environment of increased focus and attention on the expansiveness of intellectual property rights. So, perhaps you heard it here first, there is no such legal claim.

In The Great Chocolate War, as reported by Jason Voiovich, the legal claim that Hershey’s — owner of the coveted Reese’s brand — brought against Dove’s competing peanut butter and chocolate candy, was based on trade dress. Notably, there was no asserted claim of "taste infringement". No one owns the combined taste of peanut butter and chocolate, thank goodness.

That’s not to say, however, that there aren’t intellectual property rights impacting the human sense of taste. For example, with respect to trademarks, we’ve written before about the possibility of taste being the subject of a non-traditional trademark, but to the best of my knowledge, none has been acknowledged or even identified to date. If you have information to the contrary, please share your insights here.

Of course, there is a reason for the lack of or scarcity of taste trademarks. Any product intended for human consumption is unlikely a candidate for taste trademark protection given the functionality doctrine. So, Coca-Cola can’t stop another from selling a beverage that has the same taste as Coca-Cola, just because it tastes the same, unless of course, the maker of the competitive beverage hired away key Coke employees who unlawfully revealed the closely guarded secret formula. That is how trade secret litigation happens, not "taste infringement" litigation.Continue Reading Taste Infringement?