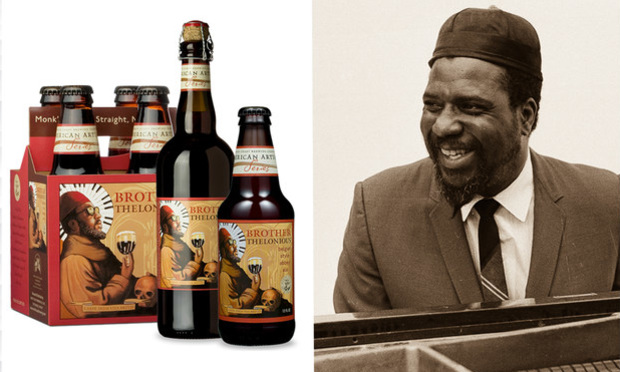

Earlier this month, a California federal judge kept alive a suit brought by the estate of famous jazz musician Thelonious Monk against North Coast Brewing Co. for trademark infringement and infringement of the right of publicity. The dispute centers around North Coast’s popular “Brother Thelonious” Beligan-style abbey ale (beer seems to be on the mind here at DuetsBlog as of late), which features a likeness of Thelonious Monk on its label:

The estate, managed by Thelonious Monk’s son, Jr., agreed to allow North Coast to use the likeness for selling the beer so long as North Coast agreed to donate some of its profits to the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. North Coast apparently upheld its end of the deal, donating over $1M to the Institute since 2006. Though, North Coast also expanded its use beyond beer, to beer brittle, goblets, hats, apparel, signs (metal, neon, and paper), playing cards, pins, and even soap (made–incredibly–using the beer).

North Coast even registered a trademark on its label design, which “consists of a profile portrait of a gentleman in a red cap, dark glasses, and brown monk’s garb holding a glass of dark beer in one hand and a human skull in the other hand, with a stylized circular black and white piano keyboard behind his head, in an abbey setting.” Sounds like Thelonious Monk, don’t you think? North Coast also has a registered trademark on the name “Brother Thelonious.” A little late to the game, the estate registered a trademark on “Thelonious Monk” this summer.

In 2016, the estate rescinded its permission to use Thelonious Monk’s likeness, and after North Coast refused to stop using the likeness, initiated its lawsuit. The district court judge denied North Coast’s motion to dismiss the case, stating that the factual record underlying the dispute needs to be fleshed out before any of the estate’s claims can be decided. Give it several months to up to a couple years before the court issues a ruling.

The estate’s lawsuit, especially the claim for infringement of the right of publicity, got me thinking about the bases for the right of publicity and the right’s applicability to celebrities who have died–sometimes referred to as “delebs.” Sadly, Thelonious Monk died in 1982. But, like many celebrities, the value of his work and likeness endure after death. Indeed, some celebrities have become bigger in death than they were in life (e.g., Tupac Shakur, Michael Jackson, and Elvis Presley). And beloved local delebs continue to make appearances:

At first glance, it seems odd that a deceased celebrity (through an estate) would have any right to control the use of likeness after death, let alone profit from it. Indeed, the right of publicity, provided under state law, is largely founded on privacy grounds, protecting the use of one’s identity in commercial advertising given the personal and private interests at stake. After death, those personal privacy interests are no longer compelling. But the right of publicity in many states is also founded on property grounds, in view of the fact that (at least for many celebrities) individuals often invest extensive time, energy, and money in promoting and creating their own personal brand. The thought is that, like other intellectual property rights, one should be able to receive the benefits of that investment (which encourages such investment in the first place). Thus, the right of publicity is based upon both privacy and property interests.

The right to publicity is recognized in over 30 states, but the scope and breadth of the right varies in each state largely because states have differing views on whether the right should be grounded in privacy, property, or both (and if both, to what degree?). Many of these states have a right of publicity statute, but some do not. For example, as I discussed previously, Minnesota does not have a right of publicity statute. In 2016, the Minnesota State Legislature considered the “Personal Rights In Names Can Endure” (“PRINCE”) Act, but never passed the bill. Have no fear, though; previously, in Lake v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., the Minnesota Supreme Court recognized the right of publicity based on “individual property” rights and “invasion of privacy,” citing Restatement (Second) of Torts § 652B (1977). 582 N.W.2d 231 (Minn. 1998).

Interestingly, because the right of publicity is a creature of state law, where a person was domiciled (residing) at the time of death controls what kind of right of publicity that person’s estate has after death. Estates for celebrities who were domiciled in Oklahoma are the most fortunate and can enforce the right of publicity for up to 100 years after death. But woe be upon an estate in Wisconsin, which bases its right of publicity on privacy interests and only allows living persons to enforce the right. The amount of time a right of publicity can be enforced after death varies dramatically state-to-state. For a helpful run-down of most states, see this useful overview.

How about in Minnesota? The PRINCE Act would have allowed an estate to enforce a right of publicity for up to 100 years, like Oklahoma’s statute. Under the common law, it remains unclear how long the right persists–though, the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota held (ironically) in Paisely Park Enterprises, Inc. v. Boxill, that the right survives death. See 2017 WL 4857945 (D. Minn. Oct. 26, 2017) (Wright, J.). How long thereafter? The Restatement (Second) of Torts doesn’t say.

The most basic takeaway from the current state of the law is that celebrities with likenesses that may have great value in commercial use should consider domiciling in states that have favorable post-mortem rights of publicity. Thelonious Monk was domiciled in New Jersey when he died, and the New Jersey right of publicity extends no longer than 50 years after death. So the estate has about 14 more years during which it can enforce the right, which Thelonious Monk may not have ever exercised in life.

By the way, if you’re interested in trying out the Brother Thelonious, it is available in two Twin Cities locations: First, and most appropriately, the Dakota Jazz Club & Rest (Minneapolis), and also at Hodges Bend (St. Paul).